|

| Robert Dalton Muir (August 7, 1926 - 1999) [Source: Castleguard] |

Again, Mary McKay’s book, Far Spread the Sparks from Cantire, provides us with a profile of yet another accomplished individual in the Reid family tree.

|

| Dalton Muir, from Far Spread the Sparks from Cantire |

Dalton Muir, the only son of George Muir and Leta Dalton, was a staff member of Canadian Wildlife Services, Ottawa, for many years. He travelled widely in the Arctic and the west and was especially known for his wildlife photography.

Born and educated in Toronto, he graduated from North Toronto Collegiate in 1945 and the University of Toronto in 1951. In 1970 he returned to Carleton University and graduated with a Master of Science degree.

His boyhood hobby of photography developed during his high school years into a fascination for capturing on film birds, especially hawks and owls. After graduation he began making science films for the National Film Board and later worked for National Parks – Environment Canada.

While at the University of Toronto he met his future wife. On October 7, 1953 he married Marianne Boyd, daughter of Arthur and Mary (Bomps) Boyd of Toronto. They had two sons: Richard (1956) and Roderick (1959).

The summer before Richard was born Dalton and an assistant, Norval Balch, spent five months on Ellesmere Island, Canada’s most northerly land mass. They made two colour films for the National Film Board Science Film Unit. These were the first such movies made in that bleak land. Dalton and Norval were flown by R.C.A.F. North Star and C-119 Box Car to the weather station at Eureka on Ellesmere Island. From there, they covered their territory by canoe, foot and plane. Being a person who prefers cold weather to hot, Dalton enjoyed the 4 degrees temperature and 24 hours of daylight on Ellesmere Island.

|

| Click to watch |

|

| Click to watch |

From 1956-1963 the family lived in Beaconsfield, P.Q., and then moved to Nepean, just outside Ottawa and Dalton continued his photography work with the Canadian Wildlife Services. Dalton was invited by the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature to visit the nest of the Great Gray Owl that had been sighted south and east of Winnipeg. Within a few days of completing his studies at Carleton University, Dalton left Ottawa by car and drove to Winnipeg. There he met Herb Copland who worked with him in the days ahead. At the nest site, working quietly, slowly and carefully, they erected a tower blind just nine feet from the sitting bird without once causing her to leave. She quickly accepted their presence and soon paid no attention to their activities. During the next five days Dalton slept in a tent less than a hundred feet away and spent about 18 hours a day in the blind located in a swampy area close to the U.S.–Canada border. They observed the birds’ hunting and feeding habits and caught the first glimpse of the three young birds when they hatched. The opportunity for close observation of this little known owl gave Dalton and his colleagues a unique insight into the lives of a family of birds of primitive instincts and stereotyped behaviour.

Dalton recorded several of his interesting adventures in Nature Canada, Canada’s nature magazine.

|

| The great gray owl (photo by Robert Taylor). In 1985 the Great Gray Owl was officially chosen as Manitoba's Provincial Bird. |

|

| Winnipeg Free Press, June 19, 1970 |

|

| Winnipeg Free Press, July 4, 1970 |

Arctic and other glaciated landscapes have been a lifelong concern of Dalton’s. In 1985 he and Derek Ford took pictures of Castleguard Mountain in British Columbia. Dalton did the photography of the above ground terrain and Derek photographed the miles of caves. Their work was published for National Parks Centennial in a book called Castleguard.

|

| Castleguard, published in 1985 |

Dalton retired in 1988 and enjoys carpentry, metal work, electronics and landscaping. He enjoys skiing in winter and he and Marianne have travelled in their van, coast to coast and into the Arctic wilderness. He likes to go places no one else has ever been. They have visited Wales, Scotland, Alaska, Labrador, Inuvik and Newfoundland. In the winter of 1992-93 they spent five months travelling from Florida to California and up the west coast.

====

Dalton passed away in 1999, and his wife Marianne died in 2014.

Castleguard remains a legacy. It is a handsome coffee table book that is also an academic study and pictorial record of a unique place in Canada. An introduction on the dust jacket reads as follows:

Beside the Columbia Icefield, in Banff National Park, lies a narrow valley. One end of the valley is a barren arctic waste, newly formed by the retreat of the ice ages. Gradually, it grades into an alpine meadow and then into a northern coniferous forest. The valley and the glaciers around it tell the story of how the landscapes of Canada were formed, from the great ice ages to this summer’s flowers.

Partway down the valley there is a cave mouth, the sole entrance to an enormous complex of vaults and passageways that winds for eighteen kilometres under the valley and glacier. In the cold darkness of the Castleguard caves water has been forming and enlarging passages for hundreds of thousands of years. Glistening white stalactites, among the purest in the world, have been growing for millennia.

Come celebrate Castleguard with the adventurers who have explored and photographed the austere beauty of this land shaped by water, cold and time.

Here are a few of Dalton’s photographs and descriptions from Castleguard:

|

| Flowers on an Alluvial Fan (photo 31)

High in the mountains, spring arrives late but fall arrives early. During the short summer, plant life develops at breakneck speed and a brief, glorious surge of blossoming appears. Only a few days after the first flowers of a species appear, the rest burst into bloom. Seed follows quickly, because an unusual early frost is always a danger. When early frost strikes, an entire year's seed production may be lost; no new plants will form and continuity of the species will depend on the survival of existing plants.

This early August scene shows the entire vertical sequence at the height of summer. At the top are the sterile mountain peaks. Below lies the central Castleguard Glacier, led by the Columbia Icefield, with its light-brown lateral moraine. Among trees of the thin alpine forest is the rocky stream that carries meltwater down to the alluvial fan. The moist, well-vegetated margin of the fan is a floral meadow in full bloom. Two days after the photograph was taken, night-time frost killed the flowers.

This setting is also a dramatic rendering of ecological succession. From barren gravel deposited perhaps a hundred years ago, a series of plant communities has progressed to become a floral meadow of species such as the showy pink legumes of the pea family and the less noticeable cream-coloured Dryas of the rose family.

|

|

| The Red Spring (photo 105)

This is how a cave begins. Water is pouring from a wide horizontal slot (a bedding plane) but the opening that has been eroded is no more than 2 to 3 cm/1 to 1-1/2 inches high. As hundreds and thousands of years go by the channel will deepen and the slot will become a cave passage several metres wide and deep.

The spring has been named "Red Spring," from the distinctive colours of the mosses and algae that grow on the cliff below it. Most springs in this region dry up during the winter, but this one flows throughout the year, dwindling to a litre or two per second, less than one percent of the July flow seen here. The water is coming through a floodwater channel from Castleguard Cave, 150 m/500 feet to the rear of the picture, and it is believed to drain parts of the southern half of Castleguard Meadows. |

|

| Time (photo 111)

The experience of Castleguard is a journey through time.

The rocks were formed hundreds of millions of years ago. The mountains are younger, pushed up by forces some tens of millions of years ago. The great glaciers passed over them repeatedly within the past few million years and just melted away about ten thousand years ago. The Little Ice Age happened within history, during the past seven hundred years. It ended during this century, within living memory. The meltback continues today. Each year winter passes over the land and changes the details of Castleguard. Late-spring storms delay the onset of growth and summer frost may end the floral display on the Meadows.

At Castleguard, we can read time in the landscape. Beneath all that is visible on the surface lies another landscape, the Cave; it too is a mirror of time.

Castleguard is a perfect embodiment of the National Parks concept: a heritage of important natural landscapes preserved for all time, while making possible recreation, discovery, insight and memories.

|

|

| Reward (photo 112)

Early adventurers dreamed of streets paved with gold. We have built a civilization that surpasses this crudely imagined luxury. Still, we search, and sometimes find a greater treasure.

The sun that burned us through the day had risen behind Terrace Mountain and flooded over the glacier nearby. At sunset it turned the opposite valley wall to gold against a threatening sky. Then, it swept the shadow of another mountain over us, over the trees beyond the stream, the valley, the huge moraines and the high valleys. It lingered briefly on remnant snows and ice that still tear at the mountains before darkening the peak. |

|

| Reflection (photo 113)

Most of us live so far from a glacier that it is nothing more than a remote object of curiosity. Yet all of Canada is a glaciated landscape. We obtain food and wood from its soils, live on it and bury each passing generation in it. As we stare past the warm glow of the fire at the sunset on the shrunken glacier across the valley, we can experience this continuum. The small, unnamed glacial remnant on Terrace Mountain, and our near one that is warmed by the rising sun, are realities that confirm our place in the natural order and link us to processes still moulding the face of earth.

|

====

You might also be wondering if Dalton Muir is related to the great John Muir (1838-1914), the naturalist and conservationist regarded as the Father of National Parks in the USA. The Sierra Club website states that Ken Burns, the documentary film maker, considered John Muir to have "ascended to the pantheon of the highest individuals in our country; I’m talking about the level of Abraham Lincoln, and Martin Luther King, and Thomas Jefferson, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Jackie Robinson – people who have had a transformational effect on who we are."

The Sierra Club website explains John Muir's importance:

"As a wilderness explorer, he is renowned for his exciting adventures in California’s Sierra Nevada, among Alaska’s glaciers, and world wide travels in search of nature’s beauty. As a writer, he taught the people of his time and ours the importance of experiencing and protecting our natural heritage. His writings contributed greatly to the creation of Yosemite, Sequoia, Mount Rainier, Petrified Forest, and Grand Canyon National Parks. Dozens of places are named after John Muir, including the Muir Woods National Monument, the John Muir Trail, Muir College (UCSD), and many schools.

|

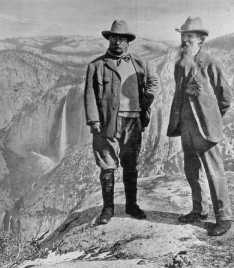

| Teddy Roosevelt (left) with John Muir |

"His words and deeds helped inspire President Theodore Roosevelt’s innovative conservation programs, including establishing the first National Monuments by Presidential Proclamation, and Yosemite National Park by congressional action. In 1892, John Muir and other supporters formed the Sierra Club 'to make the mountains glad.' John Muir was the Club’s first president, an office he held until his death in 1914. Muir’s Sierra Club has gone on to help establish a series of new National Parks and a National Wilderness Preservation System."

Dalton Muir and John Muir: if not kin, then kindred spirits. John was born in Dunbar, Scotland, on the coast east of Edinburgh. In 1849 his family moved to Wisconsin, and by 1868 he had settled in California. He does not appear to be related to the Muirs in our family tree, unless there is a distant link back in Scotland.

John Muir did, however, spend two years in Meaford, Ontario, which is in Fraser and Reid country. The young Muir worked in a Meaford mill, producing hay rakes and broom handles, from 1864 to 1866. When the mill burned down, John returned to the States. (Some say he was in Canada to avoid service in the American Civil War.)

The Meaford Museum still commemorates "John Muir Day" on the 21st of April each year, as does the state of California, in accordance with California Education Code Section 37222.1:

On John Muir Day, all public schools and educational institutions are encouraged to conduct exercises stressing the importance that an ecologically sound natural environment plays in the quality of life for all of us, and emphasizing John Muir’s significant contributions to the fostering of that awareness and the indelible mark he left on the State of California.Mark your calendars, and raise a wee toast to all the Muirs!

⇧ Back to Top