Enlisting in the R.C.A.F. required plenty of paperwork, but so did leaving the service.

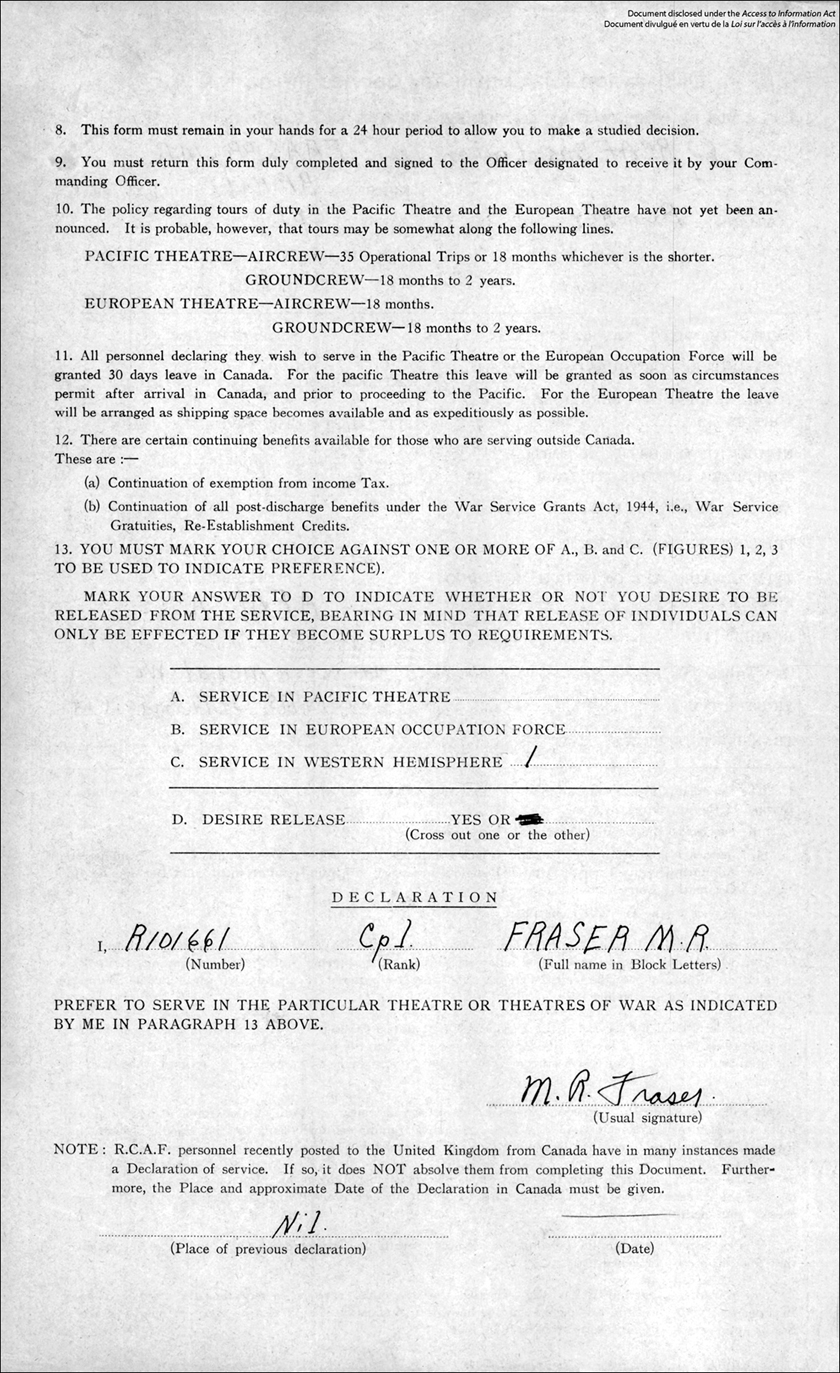

With the end of the war in sight, the air force wanted to maintain its strength and redirect its men into three other opportunities: (a) service in the “Pacific Theatre of Operations,” (b) the “European Theatre / European occupation force,” or (c) the “Western Hemisphere.” It was assumed that servicemen would choose from these three options, but the air force could override their choices. Paragraph 6 noted, “It is the intention to employ personnel in accordance with their preferences, but no guarantee can be given that this can be accomplished.”

|

| Declaration for Continuing Service in the R.C.A.F., side 1 |

Only below this directive, and half way down side two, was a fourth choice (“D. DESIRE RELEASE”) offered, with the proviso “RELEASE OF INDIVIDUALS CAN ONLY BE EFFECTED IF THEY BECOME SURPLUS TO REQUIREMENTS.”

|

| Declaration for Continuing Service in the R.C.A.F., side 2 |

Murray Fraser was not swayed, and did not need 24 hours to think it over. He chose option D. The word “No” written on the top right of side 1 was likely a clerk’s notation when sorting. Add it to that pile with all the others wanting to just go home.

And of course there were regulations associated with a discharge from the RCAF. A Discharge Certificate outlined specific rules about wearing the uniform and referenced Section 438 of the Criminal Code of Canada. Violators could risk fines and imprisonment.

The R.C.A.F.’s Discharge Certificate also warned about maintaining secrecy, even in peacetime. “All ranks are bound by the official Secrets Act to respect the confidence of much information, both during and after Air Force service, and infractions of this order would constitute a criminal offence.” This directive included the need to maintain secrecy in job interviews, for instance.

|

|

| Murray Fraser was officially discharged on February 7, 1946, and he signed the Discharge Certificate to acknowledge that he would abide by its orders. |

Upon being “honourably released and transferred to the Reserve, General Section, Class E,” he was issued the Canadian War Service Badge. It was established in 1940 “for members of the Naval, Military or Air Forces of Canada who have declared their willingness, or who have engaged, to serve in any of the said forces on active service beyond Canada and Overseas, and who have been honourably ceased to serve on active service.”

|

| The War Service Badge had its own rules, of course. Penalties for wearing it illegally or defacing it were severe. |

|

| "This Certificate must be carried whenever badge is worn." |

Cpl. Fraser, R.101661, arrived back in Canada on January 1, 1946. Before returning to civilian life, the air force gave its servicemen an exit interview of sorts, recorded on R.C.A.F. form R307 H.Q.885-R-307, below:

A March 8, 1946 letter from Group Captain T. K. McDougall to the Department of Veterans Affairs confirmed Cpl Fraser’s release from the RCAF.

|

| It's official. As of February 7, 1946, Murray Fraser had completed his voluntary service and was now a veteran. |

|

| The Application for War Service Gratuity was likely one form Murray Fraser was happy to complete. |

|

| Cpl Fraser served 1750 days in the air force (including 287 days overseas), but 141 days of "non-qualifying" leave were subtracted in the calculation for gratuity payments. |

|

| The total war service gratuity of $509.87 would be paid in five monthly payments of $101.97. |

|

| The R.C.A.F. paid $7.50 for each period of 30 days served, and an additional 25 cents per diem for overseas service. |

The comprehensive Record of Service Airmen (below) tracked every move. It listed postings, promotions, medical history, trade and character, coursework, leave, awards, and more. Movement between units was recorded as SOS (Struck off Strength) when leaving, and TOS (Taken on Strength) when joining a unit.

|

| The Record of Service summarized Murray Fraser's career in the air force. |