This wave was spurred by the Homestead Act passed by the U.S. Congress in 1862.

Ten percent of the United States, or 275,000,000 acres of land, were given to settlers under this act. Between 1879 and 1886, more than 100,000 people settled in northern Dakota. To claim 160 acres [a quarter section] of free land, a man or woman had to be head of a household and 21 years old. The homesteader had to pay an $18 filing fee and live on the homestead for 5 years. The law required that they build a house, measuring at least 10' x 12', and have at least 10 acres of land under cultivation. Immigrants from foreign lands were required to become U.S. citizens in order to claim land. [1]

Railways opened the American West in the 1870s and 1880s. The federal government gave generous land grants to the Northern Pacific Railroad to help finance their expansion. Every other section (1 section = 1 square mile) was given to homesteaders. The race was on among railway companies.

[T]he Great Northern energetically promoted settlement along its lines in the northern part of the state. The Great Northern bought its lands from the federal government—it received no land grants—and resold them to farmers one by one. It operated agencies in Germany and Scandinavia that promoted its lands, and brought families over at low cost. The battle between James J. Hill’s Great Northern Railway and Edward Pennington’s ‘Soo Line Railroad’ to control access across northern North Dakota resulted in nearly 500 miles of new track and more than 50 new town sites in one year. Many of the town sites were never settled, and were abandoned. [2]

|

| “Great Northern Railway construction crews, building track near Minot, North Dakota, 1887.” [3] |

|

| “The Northern Pacific Railroad was the first railroad to enter North Dakota. This train is hauling farm machinery to early homesteaders.” [4] |

The railroad reached Langdon in 1887 and when it was rumoured that it would continue on to Hannah, plots were surveyed and sold as townsites along the railroad. The Hannah line was one of the first to be built northwest of Grand Forks and was known as the “Wheat Line.” It was completed into Hannah, September 15, 1897. [5]

Ethnic variety characterized the new settlements. Following the first settlement “boom”, a second boom after 1905 increased the population from 190,983 in 1890 to 646,872 by 1920. Many were immigrants of Scandinavian or Germanic origin.

Norwegians were the largest single ethnic group, and after 1885 many Germans immigrated from enclaves in the Russian Ukraine. A small, but strong community of Scotch-Irish-English background played an especially influential role, contributing many of North Dakota’s early business and political leaders. [7]

By 1915 80% of all North Dakotans were immigrants or children of immigrants.

Between 1870 and 1890 more than 120,000 Canadian-born chose the American Plains over Canada, with present-day North Dakota being the most important destination within the region. […] Most Canadians migrating directly to North Dakota came from three major source regions in Ontario: the Huron Tract, Glengarry County, and Bruce and Grey counties, all areas experiencing significant population pressure. […] Transplantation of Ontario communities, as evidenced in the adoption of Canadian placenames, was made possible by processes of chain and cluster migration. [8]

The Frasers and Reids

The Frasers and the Reids had a lot in common, aside from their Scottish roots. The large families of Pete Fraser and Annie Reid had settled in the Huron district of Ontario, and half of them ventured further west.

Four of the eight children born to Douglas (1848–1915) and Catherine (Hay) Fraser (1849–1940) left Wingham, Ontario and settled in the Pilot Mound area in 1906. Annie Belle, who had been teaching in the district since 1905, was joined out west by brothers Pete, Doug, Gordon, and her parents. Siblings Sandy, Jessie, Will and John remained in “the east,” tending to their business interests in farming and horse racing.

Likewise, Peter Reid (1829–1895) and Christena (Taylor) Reid (1839–1925) had a family of nine children. Five of them—Maggie, Peter, Tena, Sandy and Annie—left their Ontario home between 1886 and 1908 to settle in Dakota Territory, across the border from Pilot Mound. They were part of a great settlement boom.

The Reid pioneers were hardy and adventurous. Farming on the American prairies, they dealt with more hardships than the Frasers. Game and determined, they were successful when half of Dakota homesteaders failed.

There were different ways to acquire land: (1) a regular homestead application for 160 acres; (2) a “tree claim” of another 160 acres of land requiring the planting of 10 acres (i.e., 6750 trees) that survived for at least eight years; and (3) a “pre-emption” claim requiring squatters to pay the government within 18 months for the land they were living on.

Another option was to buy land directly from the railroads, the government, or other land owners. An 1889 guide stated that improved farming lands could be bought for $20 an acre, and unimproved lands could be as cheap as $5 or $6 an acre, “putting a North Dakota farm within nearly everybody’s reach.” [9] The publication added that the Northern Pacific Railroad “has still for sale 7,000,000 acres of land on easy terms to settlers [that was] among the most desirable to be had, price, soil and location considered.” Prices ranged from $3 to $6 an acre for agricultural lands, and $1.25 to $4 an acre for grazing lands.

Thus up to 1890 more newcomers had acquired land by purchase than by taking advantage of the government offer of free land. […] Purchase enabled the settler to use the land at once as security for a loan, an advantage denied the homesteader until he had accumulated five years of residence. [10]

Land may have been affordable, but there were other expenses, of course. Financing a new household and farm operation was another challenge settlers faced.

Every homesteader had to build a house, dig a well, and feed the family. If they didn’t have a horse, an ox, or a milk cow, they had to borrow livestock to pull the plow until they could afford to buy a horse. A good plow horse might cost $75 in the 1880s. They also had to buy seed. One historian has estimated that the actual cost of homesteading was about $1,000 ($23,400 today). That amount covered the costs of transportation, seed for the garden and fields, livestock, and living expenses until the crops were harvested. [11]

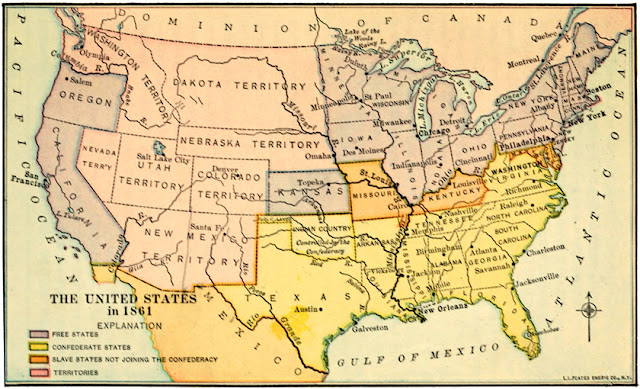

|

| A land of promise: United States in 1861. [12] |

The first intrepid homesteader in the family was 22-year-old Maggie, who travelled to Dakota Territory shortly after her marriage to 29-year-old George Muir in 1886. George grew up in Wroxeter, Ontario and had spent four years in Dakota Territory before returning to Ontario in the fall of 1885.

Travelling to the Great Plains in 1886 wasn’t easy: by boat to Port Arthur (present-day Thunder Bay), then by train through Winnipeg to Manitou, and finally by team to Edinburg, an emerging town in the northeast of the territory (109km northwest of Grand Forks). A year later Maggie and George headed northwest to a homestead three miles west of Hannah.

Mary McKay’s account describes the homestead of George and Maggie Muir:

Their first home was a sod shanty built from prairie sod and poplar poles, brought from the woods many miles away. The poles were inside to keep the sods from falling in. The roof, made of the same material, often leaked. The only lumber used was the floor and the window and door frame. To keep out the wind, the walls of the two small rooms were plastered with white clay. This kept the rain from washing the mud off the walls onto the floor. It also kept dirt from sifting in on dry days. White clay was much better than the usual mud because it was white and hard, almost like plaster and made the place look so nice. Each spring Maggie gave it a new coat of white wash. Maggie used print curtains to screen off the beds. She put white cotton curtains above the windows on the kitchen wall to make the window look full size, not like half a sash nailed in place. The window did not open for ventilation, even in summer heat.

Their furniture was homemade—a long table with a bench at each side. Bunks were necessary for beds because three of their five children were born in the sod shanty. [13]

Maggie baked pies and bread for several bachelors on nearby homesteads. These included her brother Peter Reid, who came west in 1887 at age 21. He lived with Maggie and George before establishing his own homestead.

Being neighbourly was more than a nicety. It was crucial for surviving in this harsh environment. Every cliché of pioneer existence was a very real test of endurance and a matter of survival.

|

| The soddie was only a stepping stone, as this photo of the George Muir farm in a 1912 atlas confirms. |

In February of 1895 Maggie’s father, Peter Reid Sr., died back in Ontario. She took her three children back to Canada to be with her mother, returning to Dakota in the spring.

|

| The Peter Reid Sr. farm, Elderslie Township, Ontario, where Maggie and her siblings grew up. |

Maggie was a survivor. Widowed in 1922, she outlived her son George and daughter Christina and died on February 14, 1946, at age 82. George and Maggie are buried in Hannah, North Dakota.

〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰

Also seeking pioneer adventure was Maggie Reid’s brother Peter, the third child and eldest son in the family of nine children. He was three years younger than Maggie and went west a year after she did.

Peter arrived in Dakota Territory in 1887 when he was 21 and stayed with Maggie and George Muir until he could file a homestead of his own. He built himself a one-bedroom sod home and met the other homesteading requirements. Many of the neighbouring bachelors, like Peter, were thankful for Maggie’s regular supply of baking.

On August 8, 1895 Peter married Henrietta Elizabeth Balfour, whose family had moved to Dakota Territory from Ontario in 1889. They shared a sod house with Henrietta’s grandparents, John and Eliza Balfour, near Hannah. The couple settled on their farm and soon had four sons: Austin, Neil, Russell, and Sterling.

The family farmed for seven years, moving into the town of Hannah when Peter was elected County Commissioner in 1903. Two years later, he was elected Sheriff of Cavalier County, prompting a move to Langdon. The family was lucky to avoid disaster when a hailstorm and cyclone hit Langdon on May 29, 1909. A young neighbour boy was found dead in their yard, one of five deaths reported.

In 1913 Peter was appointed to the office of Deputy Warden at the State Penitentiary, and moved his family to Bismarck, the capital of the new state of North Dakota (as of 1889).

Civic-minded Peter Reid became superintendent at the state training school in 1918. At age 62, he joined the city police force and served as night patrolman. He retired after being struck by an automobile in 1934. He never fully recovered from his injuries. Two years later, he died of a stroke on March 12, 1936.

He had lived an eventful and full life. “Peter was a jolly man with an inexhaustible fund of stories. He enjoyed a good time and a good drink. In his almost 70 years he had been a pioneer farmer, assessor, township clerk, county commissioner, sheriff, warden and patrolman.” [14]

Henrietta outlived her husband by 27 years, and was cared for in her senior years by her son Russell. She passed away at age 90, on February 20, 1963.

〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰

Born in a log house on the Reid homestead in Elderslie Township, Ontario, Sandy was the fifth child and second son of Peter Reid and Christena Taylor.

In 1892, 22-year-old Sandy followed his siblings Margaret and Peter to the new state of North Dakota (est. 1889). After arriving in Cavalier County on March 28 of that year, Sandy filed a homestead claim 4-1/2 miles southwest of Hannah. Margaret and George Muir moved from Edinburg (71 miles southeast of Hannah) to three miles west of Hannah around that time.

As a new homesteader, Sandy built a sod house and a barn, and was able to sow and harvest a wheat crop in 1893. Family and neighbours helped bachelors like Sandy. Margaret baked for several of them. In 1893 Sandy welcomed his younger sister Tena, who moved west to keep house for him.

|

| “Wanted: a lovable house keeper [...] must be kind to dogs.” Newcomer Sandy Reid might have echoed the sentiments of this bachelor camp. [15] |

The family tree added another plait to the Reid–Muir braid when 28-year-old Sandy married 24-year-old Janet (“Nettie”) Elizabeth Muir on December 1, 1898. Nettie was the youngest of nine Muir children born to George Muir Sr. (1828–1884) and Margaret Stead (1830–1891) in Huron County, Ontario. Nettie’s brother George married Maggie Reid, and another brother, Robert, was married to Mary Reid.

After her parents passed away, young Nettie travelled to North Dakota in 1892 to live with her brother Jim and his wife Mary. Six years later, Sandy and Nettie built their own sod house and established a farm on their claim. In 1903 they left the sod house when they moved to Wales, North Dakota, and moved to Hannah two years later.

In 1906 the couple moved to Saskatchewan, but returned to Hannah in 1909. Sandy worked in the Citizens’ Bank there until 1929 when the bank failed.

In January 1910, Sandy and Nettie welcomed their daughter Jean Alexandra, their only child. Sandy was 40 and Nettie was 36. Jean passed away on October 27, 1987 at age 77.

Sandy Reid lived in Hannah for 49 years (less one day), dying on March 27, 1941 at age 71. He was well regarded in the community, and many turned out to pay their respects. Following her husband’s death, his widow moved in with her daughter Jean, a registered nurse, in Valley City. Nettie passed away nine years after Sandy, aged 73. She was buried in Hannah on June 1, 1950.

〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰

Tena journeyed to Ontario after her father’s death in February of 1895, returning to Dakota in the spring. On March 3, 1897 she married James Moffatt and joined him in his sod shanty before their frame house was built. The couple had three boys: Peter, James, and Leslie.

Born on June 5, 1867, James was also from Huron County, Ontario, and had gone to Dakota Territory when he was about 18 years old. In 1888 he purchased a homestead 2-1/2 miles west of Hannah. Maggie Reid added James to the list of bachelors happy to receive her baking.

As was typical in the family, the Moffatts were civic-minded and busy citizens in Dakota. James was a Sunday School Superintendent in the Presbyterian Church for 25 years, a member of the local Ionic Lodge, and President of the Hannah Farmers’ Cooperative Elevator Company. He was a long-time school board member on the Bryon Township and also sat on Hannah’s Board of Trustees.

James and Tena retired to Hannah in 1920, leaving the farm to their son Peter and his wife Alice (née Thody). Peter’s brother Jim enjoyed a long career in banking. Leslie, the youngest, never married and remained with his parents, caring for them into their old age.

In poor health for some years, Tena suffered a stroke on March 23, 1937 and died three days later, one month after her 69th birthday. Her husband James passed away nine years later on December 2, 1946.

〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰

Annie was still a young child when her older siblings left home to marry and establish their own homes. Maggie left for Dakota in 1886, followed by Peter in 1887, Sandy in 1892, and Tena in 1893, when Annie was 12.

|

| Young Annie and her sister Kate, in Ontario. |

Fourteen-year-old Annie was in her last year of school in 1895 when her father died. The family remained in the Reid home, and Neil, Donald and Kate carried on the farm work. She visited her siblings in Dakota, returning with Maggie and George when they returned home for a visit in 1907.

The Reids were a close family, even at a distance. There was a lot of travel and correspondence between Ontario and Dakota.

|

| A postcard from 9-year-old nephew Peter Moffatt (Tena’s son) to Annie Reid, still in Gillies Hill, Ontario. It is unlikely Annie knew horses Punch and Maud, unless they were also from Ontario! |

|

| Postmarked in Hannah on July 22, 1907, the card took only three days to reach the post office in Paisley, Ontario. |

Lawn Tennis at Hannah, N. Dak., Jan. 24, 1908. This postcard sent to Annie Reid in Gillies Hill, Ontario invited her to consider moving to North Dakota.

The idea proposed in the postcard worked. When Donald married in 1908 and took over the family farm in Ontario, Annie did move to Dakota. At first she lived with her sister Tena, a couple of miles from Hannah. Later, she boarded in town, and worked at the Valentine & Schefter store from 1913 until her marriage in 1916. Having worked in a store back in Paisley, Ontario, she was an experienced saleswoman.

Annie Reid would not have appreciated the opinion of “shop girls” expressed in an 1884 article in the “Woman Gossip” section of the Pilot Mound Signal (the precursor to the Sentinel newspaper).

|

| “young ladies who have been assistants at shops do not make thrifty and helpful wives” [16] |

Pete Fraser had known Annie Reid for some years, and would drive his horses across the border from Pilot Mound to Hannah to court her. They married on July 19, 1916 at the Hannah home of Tena and James Moffatt.

|

| Annie and Pete Fraser on their wedding day, July 19, 1916. |

Moving to Dakota several years after her older siblings, Annie was not a sodbuster, and did not have to endure the same pioneer hardships. The closest she came to living in a soddie was the modest farm home just outside Pilot Mound, Manitoba. There, Pete and Annie raised their two children, Jessie (1917–1976) and Murray (1919–2013).

Annie understood the challenges of homesteading, and remained in Manitoba between 1909 and 1912 when Pete, his father Douglas Sr., and Doug Jr. laid claims near Elrose, Saskatchewan. Their western adventure taught them survival skills that Annie could have warned them about. Doug remained in Saskatchewan as an elevator agent, but Pete and his father were happy to return to the comforts of home when they cashed out.

As her son Murray Fraser wrote, “Annie was a good farm wife. She was very capable in all household chores, cooking, sewing, knitting, mending, nurturing. She would also milk cows at threshing time when the men spent long hours in the field, often at other farms when the ‘big outfit’ was operating. She kept a big garden, made her own butter and cared for the hens. She would trade eggs and butter at the stores in town to keep the family in groceries.” [17]

|

| A good farm wife,” Annie Reid Fraser with daughter Jessie (b. 1917). |

In 1951 Annie and Pete retired to a small house in Pilot Mound. It had no sewer or water, but at least had electricity and oil heat.

After Pete died on October 7, 1955 Annie lived on her own until the early 1960s, when she moved in with her daughter Jessie and her son-in-law, Jack Houlden. While standing at the sink doing dishes, one of Annie’s hips collapsed. She spent some time in the Pilot Mound hospital before being moved to Winnipeg, where she received an artificial hip. She recuperated at her son’s home before returning to Pilot Mound. In 1967 she moved to a private nursing home in Manitou. On January 28, 1969, she passed away, 23 days after turning 88.

The Land of Milk and Honey, and Other Lies

|

| Currier & Ives, “American Homestead” series, c. 1868–1869. [18] |

There were warnings about how challenging homesteading could be. An editorial entitled “A Province Gone Mad,” in the March 22, 1884 Pilot Mound Signal criticized greedy speculators and their unrealistic expectations:

[A]varice has destroyed the senses of the people. The very wealth and richness of the country has made men dizzy with greediness. Not contented with a living and a good one, almost every one is panting to be rich. The temptation to raise wheat is something which few can resist. Farmers sow more than they can get in until seed time is over, and more than they can cut and save properly before the harvest season is ended. […] Inflation and financial madness was in the addled brain of every excited idiot who went by the name of speculator. The fever spread until even the usually cool heads of the farmers are whirling, and not a few have lost their feet as well as their judgment. Only one or two things could avert national disaster brought on by national greediness. The only cure was frost or grasshoppers, and nature kindly sent the lesser evil, which was really a blessing in disguise. […] There are by far too many expensive agricultural implements in the country already—more than the people can use profitably, more than they can shelter from the rains of summer and the snow storms of winter, and more than they can pay for. [19]

Editor John A. Murdoch concluded that, “The production of grain should be limited until such time as the country is more properly settled, elevators erected, and railways extended,” to “wholly avert evil brought on by recklessness and imprudence on the part of the people.” He believed that newcomers from Ontario, used to clearing brush and dealing with poor soil, were overly excited by the rich open prairies just begging to be farmed.

Manitoba was competing for immigrants to settle the prairies, and resented the choice to head to Dakota instead. Canadian editors warned of the challenges immigrants faced in America. In 1890 the Winnipeg Tribune reported that, “the republic is not exactly a garden of Eden. The glowing anticipation of a land flowing with milk and honey, which many Canadians entertained as they started for the Western States, have been rudely dispelled.” [20] The Tribune called for honesty, criticizing promoters and “sordid boosters” for misleading newcomers. The situation was “reprehensible from an ethical point of view,” [21] and new American settlers were bound to discover the hard truth.

An unsigned letter to the Canadian Statesman published July 20, 1883 in Bowmanville (68 km east of Toronto) was titled, “Dakota No Paradise,” as “a note of warning to some of your readers who may intend to remove to the much-over-praised Dakota.” The letter referenced the Chicago Journal in its assertion that “Dakota is not the land of promise, flowing with milk and honey, which many people have been led to believe.” [22]

The story of Dakota has been in some respects altogether too highly colored; the emigration business has been entirely overworked, the excitement is about over, and now comes the relapse. […] the climate is too severe […] when wells 20 feet deep are frozen over, and winter sets in about the first of October with a coldness that defies the registry of Fahrenheit and continues until May […] There is a heavy emigration to this territory, and much of it is landgrabbing in nature. […] And many a honest pioneer takes his claim, toils to make a home, and in a year or two finds himself almost isolated from the blessings of society. [23]

Experience taught ranchers and homesteaders immediately that the Dakota Territory was not God’s country. Some would consider it hell. And yet, as late as 1919, writers continued to praise it as the land of milk and honey.

A 1919 book, North Dakota of Today, [24] was dedicated to Teddy Roosevelt, “A North Dakota Man of the Old Days; Whose Memory shall Ever Live in the Hearts of North Dakota People.” It flattered the state as well as the ex-president. Any resident would find its exaggerations laughable.

|

| Fresh breezes (not tornadoes). Streamlets (not floods). Whiter snows (not blizzards). Dakotans and Roosevelt knew otherwise. |

Not surprisingly, historian Ray H. Mattison of the Theodore Roosevelt National Memorial Park would not endorse Trinka’s writing, stating, “It is my opinion that, from the standpoint of historical accuracy, her books are not of a very high quality.” [25] She also wrote to state historian Russell Reid, whose reaction can be guessed.

The Hard Truth

Those leaving a civilized life in Ontario soon discovered that homesteading was tougher than they anticipated. Fewer than half of homesteaders succeeded. Homesteaders in Dakota had to stay on the property for five (later three) years, break sod to cultivate at least 10 acres, and build a habitable dwelling. These sodbusters had to contend with isolation, bad (or no) roads, spring floods, summer droughts, tornadoes, hail, rust, prairie fires, wicked winters, gophers, mosquitoes and other assorted pests.

Farmers cursed the grasshoppers that could invade and devour entire crops. It was reported that they were “so thick that in 1883 the NP [Northern Pacific] locomotive wheels slipped on rails greased by mashed grasshopper bodies.” [26] Settlers reported swarms a mile high and a hundred miles across.

They cursed gophers, too. One writer to the North Dakota Farmer newspaper in 1888 told of his method of poisoning gophers, using “Rough on Rats” tainted corn kernels in containers with holes too small for cats and fowl. He wrote that he could “clear a whole section of land of gophers in one day with from thirty to fifty cents worth” of poison. [27]

Homestead requirement or not, the unforgiving climate demanded that building a house was the first priority. Sometimes their initial shelter was a dugout. They lived on the land and in it. A pine board shanty could be constructed where timber was available, but often a homesteader’s first home was a primitive sod house (or “soddie”). Strips of sod, about two or three feet long were laid into walls about three feet thick around a log framework if trees were available. A framed door and window or two were added. The house was typically roofed with rough lumber and heavy tarpaper, slough grass and sod, or perhaps shingles. Interior walls plastered with mud and ashes were often covered with cotton or newspaper pages to help make them windproof and clean. Soddies were warm in winter, cool in summer, but not impervious to dirt, heavy rain or vermin. [28]

|

| “Early homesteaders gather for a visit near a sod home. (SHND CO694)” [29] |

|

| Mary (Haumont) and Theodore Frischkorn, 1888, in Custer County, Nebraska, the “Sod House Capitol” of the world. The cat was a good idea, considering the rodents around. [30] |

|

| Nebraska dugout, 1870. Dug into a hill, such temporary homes were cheaper to build. They typically faced southeast to catch summer breezes and shelter from winter winds. [31] |

|

| “Interior of a sod home showing the kitchen area. (SHSND B0378)” [32] Newspapers brighten the walls and help control the dirt. |

Winter on the Great Plains

|

| Another romanticized Currier & Ives print, “The Snow-Storm,” c. 1864. [33] |

Many newcomers underestimated the fierce, even deadly winters on the Great Plains. Promoters and land agents certainly never warned them. Prairie dwellers were no strangers to harsh winters, but storms in the 1880s were especially severe. The decade came to be known as the Little Ice-Age.

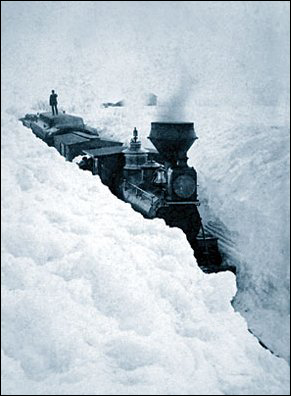

|

| “Opening the road in 1881,” a different version of winter on the Great Plains. [34] |

The winter of 1880–81 began with a South Dakota blizzard in mid-October that lasted three days. One of the coldest and snowiest winters on record, it is known as the “Long Winter” or the “Hard Winter” and lasted into April of 1881. Spring floods followed several blizzards that winter, changing the course of the Missouri River in Omaha, and washing away the town of Yankton, South Dakota. [35]

|

| “On March 29, 1881 snowdrifts in Minnesota were higher than locomotives.” [36] |

|

| Homestead after a blizzard. [37] |

|

| Home in Wahpeton, North Dakota. [38] |

|

| On the prairies, winter can last half a year. CPR track between Pilot Mound and Wood Bay, Manitoba, April 17, 1907. [39] |

It seemed winter storms like the Great Plains Blizzard of 1887 were all too common.

January 9–11, 1887. Reported 72-hour blizzard that covered parts of the Great Plains in more than 16 inches (41 cm) of snow. Winds whipped and temperatures dropped to around –50°F (–46°C). So many cows that were not killed by the cold soon died from starvation. When spring arrived, millions of the animals were dead, with around 90 percent of the open range’s cattle rotting where they fell. Those present reported carcasses as far as the eye could see. Dead cattle clogged up rivers and spoiled drinking water. Many ranchers went bankrupt and others simply called it quits and moved back east. The “Great Die-Up” from the blizzard effectively concluded the romantic period of the great Plains cattle drives. [40]

Almost a year later to the day, the Schoolhouse Blizzard [41] struck the Great Plains. It would be one of the worst in American history. On January 12, 1888 the day started out deceptively warm. People ventured out without their coats, enjoying the welcome thaw. But the cruel blizzard arrived suddenly in the afternoon, catching everyone unaware with temperatures dropping quickly to –40° (–58°F recorded in Neche, Pembina County), with strong 80mph winds and heavy snow that was fine ice crystals. Visibility was zero. At least 235 perished, with some estimating hundreds more. It was called the Schoolhouse or Children’s Blizzard because about half of the fatalities were schoolchildren.

Newspapers from far and wide, like the Winnipeg Free Press, reported on the blizzard over several days as shocking details were received. [42] There were several instances of individuals freezing to death, and many bodies in snow drifts would not be found until the spring thaw. One farmer who went to his well to water his livestock perished only 12 feet from his house. Another man who ventured out to buy coal barely made it home after his team of horses suffocated in the snow and wind. He discovered that his wife had given birth in his absence.

The Winnipeg newspaper took exception to the idea that the storm had come from Manitoba, noting on January 24, 1888, “Not a single life was lost in this Province during the late storm while over a hundred perished in Dakota alone. The death roll for the whole territory south of us will run up, in all probability, to nearly if not quite, three hundred when final reports are in; already it is over two hundred and fifty.” [43]

Arriving in 1892, Sandy missed the monster blizzard of 1888, but other prairie snowstorms made him question his choice to leave Ontario.

A blizzard of 1895 almost had Sandy convinced that North Dakota was not the place to be. The blizzard was so bad that when the men went out to do chores, ropes were tied around their waists and fastened to the house to make sure that they would find their way back when their work was done. However, with the arrival of spring, this was forgotten. [45]

Hannah, North Dakota

Like many farm towns, Hannah owed its existence to the railway.

|

| 1906. The proposed extension from Hannah did not materialize, and there remained no railway connection to Pilot Mound. [46] |

|

| A bustling thoroughfare in Hannah, North Dakota. [48] |

|

| 1915 |

|

| Main Street West, Hannah, c 1916 [expired eBay post] |

|

| Early postcard of Hannah. [expired eBay post] |

Aerial photos taken in 1963 reveal a still healthy small town. [49]

|

| “Aerial over Hannah, N.D.,” Item NDBC-17-12 |

|

| “Aerial over school, Hannah, N.D.,” Item NDBC-17-15 |

|

| “Aerial over elevator and depot, Hannah, N.D.,” Item NDBC-17-13 |

|

| Present-day Hannah (Apple maps). Scars identify the former railway tracks and the grid hints at several buildings long gone. |

|

| Six of the nine Reids in Pilot Mound, c. 1934. L-R: Annie (Reid) Fraser, Mary (Reid) Muir (visiting from Ontario), Tena (Reid) Moffatt, Peter Reid, Maggie (Reid) Muir, Sandy Reid |

Perhaps Zena Irma Trinka’s epilogue [51] is fair. We’ll allow her some poetic licence and give her the last word:

The State of North Dakota

Yes, I love it, dearly love it, with a heart that’s true as steel,

For there’s something in Dakota makes you live and breathe and feel;

Makes you bigger, broader, better, makes you know the worth of toil;

Makes you free as are her prairies and as noble as her soil.

Makes you kingly as a man is; makes you manly as a king;

And there’s something in the grandeur of her season’s sweep and swing;

That casts off the fretting fetters of the East and makes you blest

With the vigor of the prairies—with the freedom of the West!

- Lincoln’s Legacy / Homestead Act. https://www.history.nd.gov/lincoln/land5.html

- “History of North Dakota,” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_North_Dakota

- State Historical Society of North Dakota, North Dakota Studies, Early Settlement of North Dakota, “Section 9: Railroads”. https://www.ndstudies.gov/gr4/early-settlement-north-dakota/part-1-early-settlement-north-dakota/section-9-railroads

- State Historical Society of North Dakota, North Dakota Studies, Early Settlement of North Dakota, “Section 9: Railroads,” https://www.ndstudies.gov/gr4/early-settlement-north-dakota/part-1-early-settlement-north-dakota/section-9-railroads

- Mary McKay, Far Spread the Sparks from Cantire, 1993, p. 174.

- Railway Poster 1870s, Amazon Canada. https://www.amazon.ca/Railway-North-Western-Promoting-Homestead-Territory/dp/B07C8NWH84

- “Summary of North Dakota History—American Settlement,” State Historical Society of North Dakota. https://www.history.nd.gov/ndhistory/settlement.html

- David J. Wishart, ed., “Anglo Canadians,” Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska, 2011). http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.ea.002.xml

- South Dakota. Commissioner Of Immigration, Hagerty, F. H. & North Dakota. (1889). The state of North Dakota: the statistical, historical, and political abstract. Aberdeen, S.D. Daily News print. Library of Congress 32014281, https://www.loc.gov/item/32014281/

- Erling Nicolai Rolfsrud, The Story of North Dakota (Alexandria, Minnesota: Lantern Books, 1964), p. 150.

- State Historical Society of North Dakota, North Dakota Studies, Section 5: Homestead Farms. https://www.ndstudies.gov/gr8/content/unit-iii-waves-development-1861-1920/lesson-2-making-living/topic-3-farming/section-5-homestead-farms

- McLaughlin, Andrew Cunningham, “The United States in 1861,” [from old catalog], Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_history_of_the_American_nation_%281919%29_%2814779345661%29.jpg

- Mary McKay, p. 64.

- Mary McKay, p. 100.

- Christa Van Daele, ed., Harvest Yet to Reap: History of Prairie Women (Toronto, Ontario: Canadian Women’s Educational Press, 1976), p. 27.

- “Shop Girls as Wives,” Pilot Mound Signal, March 1, 1884, p. 2.

- Mary McKay, p. 311.

- Currier and Ives, “American Homestead” series, c. 1868–1869. Mutual Art. https://www.mutualart.com/Artwork/AMERICAN-HOMESTEAD--SPRING--AUTUMN--WINT/B29B33602B33DF24

- John A. Murdoch, “A Province Gone Mad,” Pilot Mound Signal, March 22, 1884, p. 1.

- “Canadians in the West,” Winnipeg Tribune, July 2, 1890, p. 2.

- “Stupid Misrepresentation,” Winnipeg Tribune, August 11, 1890, p. 1.

- Not to be confused with “The Great Blizzard” (aka “King Blizzard”) that struck the New England coast in March, 1988. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Blizzard_of_1888

- “Dakota No Paradise,” Bowmanville Canadian Statesman,” July 20, 1883, p. 1.

- Zena Irma Trinka, North Dakota of Today (Bismarck, ND: Bismarck Tribune Publishing Company, 1919), p. 27. https://www.loc.gov/item/20001905/

- Theodore Roosevelt Center, “Memorandum from Ray H. Mattison to Allyn F. Hanks,” April 25, 1950.” (Dickinson, ND: Theodore Roosevelt Center). https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o20970

- Erling Nicolai Rolfsrud, The Story of North Dakota (Alexandria, Minnesota: Lantern Books, 1964), p. 211.

- “Rough on Gophers,” Bowmanville Canadian Statesman, May 30, 1888, p. 3.

- For details of sod construction and a field study of surviving examples, see: Andrea R. Kampinen, The Sod Houses of Custer County, Nebraska, 2008. https://getd.libs.uga.edu/pdfs/kampinen_andrea_r_200805_mhp.pdf

- State Historical Society of North Dakota, North Dakota Studies, Early Settlement of North Dakota, Part 3: North Dakota Pioneers / Section 4: Homes. https://www.ndstudies.gov/gr4/early-settlement-north-dakota/part-3-north-dakota-pioneers/section-4-homes

- Ruth Wiechmann, “Homeland—Fall 2023 | Building History: Sod Walls and Appreciation for Pioneers,” Tri-State Livestock News, October 10, 2023. https://www.tsln.com/news/special-interest/homeland/building-history-sod-walls-and-appreciation-for-pioneers/

- Solomon Devore, photographer. “J.D. Semler, near Woods Park, Custer County, Nebraska,” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.08370/

- State Historical Society of North Dakota, North Dakota Studies, Early Settlement of North Dakota, Part 3: North Dakota Pioneers / Section 4: Homes. https://www.ndstudies.gov/gr4/early-settlement-north-dakota/part-3-north-dakota-pioneers/section-4-homes

- Currier and Ives, “The Snow-Storm,” c. 1864. Art Institute of Chicago. https://www.artic.edu/artworks/61279/the-snow-storm

- Barbara Mayes Boustead, Martha D. Shulski, and Steven D. Hilberg, “The Long Winter of 1880/81” Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/bams/101/6/bamsD190014.xml

- “Hard Winter of 1880–81,” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hard_Winter_of_1880–81

- “Hard Winter of 1880–81,” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hard_Winter_of_1880–81#/media/File:Train_stuck_in_snow.jpg

- Carole Butcher, “February 28: Severe Winter.” https://news.prairiepublic.org/podcast/dakota-datebook/2024-02-28/february-28-severe-weather

- Tully Brown Collection, North Dakota State Archives. https://www.flickr.com/photos/northdakotahistory

- Pilot Mound Museum, Inc., Captured Memories: A Pictorial History of the R.M. of Louise, 2000, p. 65.

- “Blizzard,” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blizzard

- “Schoolhouse Blizzard,” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schoolhouse_Blizzard

- “The List Increasing: Reports of Death From Frost in Minnesota and Dakota Still Coming in,” Winnipeg Free Press, January 19, 1888, p. 1.

- “Whose Blizzard Was It?” Winnipeg Free Press, January 24, 1888, p. 2.

- Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, “Our Story: American History Stories / Life in a Sod House,” (website retired in 2024).

- Mary McKay, p. 175.

- “Hannah Extension,: Winnipeg Tribune, May 16, 1906, p. 7.

- W. H. Shepard, Hannah Moon, May 2, 1913. Calling itself the “Official paper of Cavalier County,” the paper was published from 1913 to 1919, when a new state bylaw designating a single newspaper in each county forced its closure.

- “Hannah, North Dakota,” Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/groups/314867199403831/?_rdr

- Collection 10575, Zenith Air Photographs, North Dakota Heritage Center and State Museum

- Ghosts of North Dakota. https://ghostsofnorthdakota.com/category/hannah-nd .

- Zena Irma Trinka, North Dakota of Today (Bismarck, ND: Bismarck Tribune Publishing Company, 1919), p. 153. https://www.loc.gov/item/20001905/

See also, The Reid family tree