|

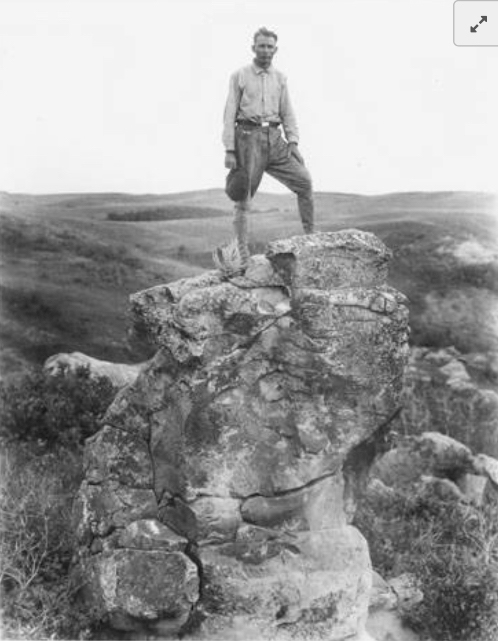

| George W. Peck [Source: Famous Wisconsin Writers, by James P. Roberts] |

|

| Lieutenant George W. Peck [Source: http://georgewpeck.com/gpbio.html] The GeorgeWPeck.com website is comprehensive and worth a look. |

After the war, Peck worked for a number of newpapers. In 1874 he founded The Milwaukee Sun. Within 10 years the weekly paper had an astounding nation-wide circulation of more than 80,000.

The Sun included Peck’s sketches featuring a bad boy named Hennery. They were very popular, and in 1883 the stories were collected into a book called Peck’s Bad Boy and His Pa. George Peck soon became a household name.

The text is a product of its day, and pokes fun at all corners of society. Some were appalled at Peck’s treatment of Victorian mores, temperance, politics, the church, freemasons, and class distinctions. The book is politically incorrect and often violent, but always hilarious.

George Peck introduced the Bad Boy to his readers:

Each chapter typically begins with Hennery, the Bad Boy, entering the local grocery shop. He might be limping or sporting a black eye. He explains to the grocer how his latest punishment is the result of yet another prank pulled on his long-suffering father, George. A chum is often his partner-in-crime.

While recounting his latest story, Hennery typically swipes some food from the grocer, who then quietly charges several times the amount to the Peck account. Before he leaves, the Bad Boy moans that a boy can’t have any fun anymore.

As he goes out the door, the Bad Boy might put out a sign in front of the grocery. The grocery man learned to check for these:

- FRESH LETIS, BEEN PICKED MORE’N A WEEK. TUFFER’N TRIPE.

- SPINAGE FOR GREENS, THAT THE CAT HAS MADE A NEST IN OVER SUNDAY.

- CASH PAID FOR FAT DOGS.

- YELLOW SAND WANTED FOR MAPLE SUGAR.

- SMOKED DOG FISH AT HALIBUT PRICES, GOOD ENOUGH FOR COMPANY.

- WORMY FIGS FOR PARTIES.

- STRAWBERRIES, TWO SHILLINGS A SMELL, AND ONE SMELL IS ENOUGH.

- SPOILED CANNED HAM AND TONGUE GOOD ENOUGH FOR CHURCH PICNICS.

It is easy to imagine Dad chuckling at Hennery’s pranks. Although never taken to task by his own father with a bed slat, Dad admitted to a few Peck-ish pranks of his own:

- teasing his dog (tapping on the floor to indicate food that wasn’t there, prompting the poor Collie to bite the floorboards in frustration);

- putting cut-up elastics in his sister’s party sandwiches; and

- hooking up a car battery to an old sow’s fence, causing the crippled, arthritic animal to sprint for the first time in years.

There are some great phrases in the book that were certain to make Frasers laugh.

As the Bad Boy tells the grocery man:

In the morning he [Father] took me into the basement, and gave me the hardest talking to that I ever had, with a bed slat.

I am going to work in a glue factory, where nobody will ever come to see me.

… and if it hadn’t been for these pieces of brick [in his britches] he would have hurt my feelings. […] I have a good notion to take some shoemaker’s wax and stick my chum on my back and travel with a circus as a double headed boy from Borneo. A fellow could have more fun, and not get kicked all the time.

Well, good day. There’s a Italian got a bear that performs in the street, and I am going to find where he is showing, and feed the bear a cayenne pepper lozenge, and see him clean out the Pollack settlement. Good bye.

… and we went home and Pa fanned the dust out of my pants. […] Well, good bye. I am going down to the morgue to have some fun.

Say, don’t you want to hire me for a clerk? The grocery man said he had rather have a spotted hyena, and the boy stole a melon and went away.

… he made me wear two mouse traps on my ears all the forenoon, and he says he will kill me at sunset.

[after being dumped by a girl]:

I shall never allow my affections to become entwined about another piece of calico. It unmans me, sir. Henceforth I am a hater of the whole girl race. From this out I shall harbor revenge in my heart, and no girl can cross my path and live. I want to grow up to become a he school ma’am, or a he milliner, or something, where I can grind girls into the dust under the heel of a terrible despotism, and make them sue for mercy. To think that girl, on whom I have lavished my heart’s best love and over thirty cents, in the past two weeks, could let the smell of a goat on my clothes come between us, and break off an acquaintance that seemed to be the forerunner of a happy future, and say “ta-ta” to me, and go off to dancing school with a telegraph messenger boy who wears a sleeping car porter uniform, is too much, and my heart is broken.

[after polluting the house and church with limburger cheese]:

I want to board at a hotel, where you can have a bill-of-fare and tooth picks, and billiards, and everything. Well I guess I will go over to the house and stand in the back door and listen to the mocking bird. If you see me come flying out of the alley with my coat tail full of boots you can bet they have discovered the sewer gas.

|

| Illustration by True Williams, 1900 edition |

The grocery man to the Bad Boy:

Didn’t you hang up that dead gray tom cat by the heels, in front of my store, with the rabbits I had for sale? I didn’t notice it until the minister called me out in front of the store, and pointing to the rabbits, asked what good fat cats were selling for. By crimus, this thing has got to stop. You have got to move out of this ward or I will.

Look here, young man, don’t you threaten me, or I will take you by the ear and walk you through green fields, and beside still waters, to the front door, and kick your pistol pocket clear around so you can wear it for a watch pocket in your vest. No boy can frighten me by crimus.

George Peck’s books were illustrated by the best cartoonists of the day. The first edition (1883) was illustrated by Gean Smith (1851-1928). He was actually known as a great painter of horses, and his paintings still come up on art auction sites.

|

| Cover of First Edition (1883), illustrated by Gean Smith |

|

| Pa battles hornets, by Gean Smith, 1883 [Source: Gutenberg project] |

|

| The Bad Boy loses his job at a drugstore. Illustration by True Williams, 1900. |

Other books in the series were illustrated by artists George Frick (listed as “C. Frick” in The Grocery Man and Peck’s Bad Boy, 1883) and Louis F. Braunhold (Peck’s Bad Boy With the Circus, 1905). Braunhold was known for his detailed Civil War etchings. The best-known illustrator of Peck’s books, however, was likely Charles Lederer.

|

| Self-portrait by Charles Lederer [Source: Wikimedia] |

|

| Illustration by Charles Lederer, from Peck's Bad Boy in an Airship, 1908 |

|

| Advertisement for Peck's Bad Boy and His Pa |

Several editions followed, and multiple publishers produced subsequent works by George Peck, including The Grocery Man and Peck’s Bad Boy (1883), Peck’s Bad Boy Abroad (1905), The Adventures of Peck’s Bad Boy (1906), Peck’s Bad Boy with the Circus (1906), Peck’s Bad Boy with the Cowboys (1907), and Peck’s Bad Boy in an Airship (1908).

Comedy troupes in the 1890s adapted the stories to the stage, and the Bad Boy went on to movies, board games, comic books, magic lantern slides, and the theatres.

A 1921 movie starred Jackie Coogan (a year after starring in Chaplin’s The Kid).

|

| Movie poster, 1921 |

|

| The humourist George Wilbur Peck, looking humourless. [Source: Wikipedia] |

Peck reestablished The Sun in 1899, but folded operations a year later, blaming cheaper magazines and daily papers. He turned his attention to writing more Bad Boy books.

Peck was also a businessman and real estate entrepreneur. As president of the San Pedro Rubber Plantation Company of Milwaukee, he planned to develop rubber production in Mexico. In 1911 he became treasurer of Independence Life of America.

He died at age 75 in 1916 of Bright’s (kidney) disease.

Civil war veteran, publisher, author, freemason, mayor, governor, entrepreneur. As accomplished as he was, George Peck will always be best known for Peck’s Bad Boy.

= = = = =

The book remains a popular read and is an interesting study in American literature of the age. Access the full, illustrated text of Peck’s Bad Boy and His Pa at any of these links:

https://archive.org/search.php?query=Peck%27s%20Bad%20Boy%20and%20His%20Pa

:: A scan of an original 1900 edition

:: Illustrations by True Williams

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015091100027;view=1up;seq=130

:: A scan of an 1893 edition, downloadable as a PDF

:: Illustrations by True Williams

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/25487

:: New typesetting

:: HTML, Kindle and other file formats available

:: Illustrations by Gean Smith (1883)