|

| The Long Tramp as we known him today, at 2579 Portage Avenue at Aldine Street, Winnipeg. [1] |

You can’t miss him. The Long Tramp is famous, as is Carman Ruttan, who at one point had his name painted across the full length of his drug store.

|

| Carman Ruttan’s mural is considered Winnipeg’s oldest. It changed over the years, but remains a favourite. (WFP, July 26, 1975) |

A history book published by the Manitoba Pharmaceutical Association in 1954 states that Carman Ruttan established his store at 2579 Portage Avenue in 1921, soon after graduating in 1919. [3] However, the business first appears in the Henderson Directory in 1923, [4] and an advertisement placed by Carman Ruttan in 1938 celebrated 25 years of pharmaceutical study, which matches the 1923 date.

The mural itself, added after the business was firmly established, is harder to date. The original artist of the Long Tramp was Leslie Charles Smith, the son of loyal customers. Smith once worked for MacDonald Aircraft before opening his own painting business. Born on October 23, 1914, the artist was about 21 at the time, which dates the mural to around 1936. [5]

|

| Leslie Charles Smith, the artist of the original Long Tramp. [6] |

|

| 1936 was a notable year for Carman Ruttan. (WFP, July 7, 1947) |

|

| “54 miles west to the next drug store.” The earliest known photo of the Long Tramp, c. 1941. The small sign between the tramp and the window advertises Ex-Lax. [8] |

The pharmacy was clearly like no other. Its windows were always covered, hours were limited, and its products were unique. The business was successful and became well-known far and wide. He served distant customers by mail, and encouraged local folks to place orders that way in bad weather.

Arnott reminisced about visiting the drugstore, a cheaper alternative than a doctor’s visit in the days before socialized medicine:

It was dark in there because it was all dark wood. There were shelves all around the room, and it always smelled good. Carman wore a white coat, like a doctor. Every time we walked in the door he’d say, “Well, I declare!”

Mom used to get a vitamin mixture from him—“beef, iron, and wine.” It looked like blood and it was awful stuff. [9]

In 1974 Winnipeg Free Press columnist Jimmy King recalled his childhood days at the drug store:

Ruttan’s apothecary shop was our meeting place, malt shop, and general hangout. Even then the colorful druggist had an international reputation and did a mail order business from all over the world. Carman Ruttan was a great jazz enthusiast and we used to discuss famous musicians and the latest recordings whenever we had a chance to chat. [10]

Early on, Ruttan advertised regularly, using small classified ads. He expressed every confidence in his medicines, and guaranteed results. He was especially proud of his poison ivy remedy and cure for stomach problems. He even offered products for horses, and could remedy the pesky affliction of—being a woman.

Ad copy from the 1930s Winnipeg Free Press (WFP) and the Winnipeg Tribune (Trib) tells of the wide range of products and services he offered:

- Any herb unobtainable elsewhere. (WFP, Mar. 19, 1932)

- Kill Poison ivy, Poison oak and like skin irritation in four days and enjoy complete immunity for balance of season. Treatment both internal and external. Complete. $1.00. Results guaranteed by graduate druggists. (Trib, Aug. 11, 1934)

- Definite stomach complaints—Definite results in a definite period. Take Sto-Sal—absolutely different. Results guaranteed by graduate druggists. (Trib, Aug. 11, 1934)

- Carman-Ruttan Drug Co. Manufacturers, dispenses, imports a complete line of homeopathic treatments. Phone 62 919 for delivery. (WFP, May 15, 1934)

- Age never dates a woman. Prolonged stubborn headaches, hysteria, frayed, high strung nerves, skin disturbances, profuse menstruation, embarrassing disturbance of moisture glands, irregularities of all kinds result from working conditions or menopause. Easy and quickly corrected naturally with Colloidal Remedy. Results guaranteed by Graduate Druggists. (Trib, Oct. 31, 1936)

- Kill poison ivy, poison oak, hay fever, ragweed, plant allergies, in five days. Enjoy complete immunity for balance of season. $1.00 complete internal treatment. Results guaranteed by Graduate Druggists. (Trib, June 2, 1937)

- To veterinary doctors in Manitoba. We believe we have a remedy that will check this new horse ailment. Sent on approval to the first 23 requests. Check progress at once. Effective in 5 days Carman-Ruttan, Graduate Druggists, Winnipeg. The most complete drug store in Western Canada. (WFP, Aug. 28, 1937)

- Imagine a stomach treatment so perfect that it works where other remedies fail. That’s “STOSAL”—Carman-Ruttan’s own original study. May be given to children. Harmless, yet positive in effect. Assists nature. No case too difficult. Carman-Ruttan, Graduate Druggists, Winnipeg. “The Chemists that made Poison Ivy harmless.” (Trib, Oct. 13, 1937)

- Chromic coughs, bronchitis, disorders of respiratory tract yield readily to Vitamin and Colloidal treatment. Entirely different, entirely definite in action. Effective through special study as to type with Colloidal Chemics (Ruttan). (Trib, Aug. 16, 1938)

- The pores of skin are exits, not entrances. To correct certain skin disorders, plant allergics, blood conditions permanently, it is necessary to correct the blood with Colloidal Chemics (Ruttan) internally. (Trib, Mar. 16, 1938)

- Kill Poison Ivy … Poison Oak … and like skin allergies in five days. Enjoy complete immunity. $2 complete internal treatment. Results guaranteed by graduate druggists. Allergies, sensitivities, immunity metabolism, being closely related, are responsible for entirely different remedies in hay fever, ragweed, poisoning, certain respiratory ailments, such as asthma, bronchitis, certain rheumatism and arthritic complaints, stomach disorders and hemorrhoids. (WFP, June 13, 1938)

- Carman-Ruttan, the first pharmaceutical chemists in Canada–U.S.A. to discover internal treatment for Poison Ivy. Still the first to guarantee results in all cases. The following home remedies are highly recommended because they serve a definite purpose—because they are advanced pharmacological process—because they are harmless, yet exact remedies for both cause and effect in the majority. Hay Fever Antigen, Poison Ivy Antigen, Ragweed Antigen, Allergy Antigens for both Skin and Respiratory Complaints, Skin Metaboloids, Respiratory Metaboloids for certain asthmas, Rheumatic Metaboloids and Sto-Sal Stomach Remedy gives a natural stomach balance without upsetting other secretions—contains no soda or bismuth and gives results because it assists Nature with tonic effects. Our formulae have always been different, having been developed entirely by us during a period of twenty-five years thorough and extensive pharmaceutical study. (WFP, Aug. 22, 1938)

- Carman-Ruttan Pharmaceutical Chemists, Winnipeg. Said to have the largest assortment of herbs in Canada. Anything difficult to manufacture or otherwise unobtainable pharmaceutically. We manufacture a kidney remedy of exceeding virtue. (WFP, Feb. 21, 1939)

- Why Hay Fever? Why Poison Ivy? Why Ragweed? Why sensitivities of the skin and respiration? Pharmaceutical Science has a simple positive answer. (WFP, Aug. 17, 1939)

|

| Interior of Carman Ruttan pharmacy, c. 1942 [stills from video] |

As Carman Ruttan’s reputation grew, so did his business. He did well enough by the 1950s to move his home and business to a newer two-storey brick building on busy Madison Street at Portage Avenue.

The building at 2579 Portage was put up for sale in December 1950. The property was soon rented to Jack Andrews, who lived and operated his own drugstore there until 1957.

|

| The building was leased, not sold. (WFP, Dec. 20, 1950) |

|

| 2579 Portage Avenue operating as Jack Andrews Drugs, c. 1955. The Long Tramp was repainted by Jack Andrews himself. [11] |

Jack Andrews became a tenant in the building and he liked the long tramp sign, which had become faded by this time. Mr. Andrews was a sign painter by trade also, so he repainted it! Pharmacists in those days would do their own signs, and Jack was quite talented at it. Eventually Andrews got into a dispute with Carman Ruttan about the tramp, because Ruttan wanted to be paid a royalty on the use of the Tramp; he saw that the Tramp was ‘working for’ Andrews. Andrews, on the other hand, had the feeling that he had brought the Tramp back to life and was already paying rent to Ruttan—he wasn’t about to pay any more. That is certainly part of the reason that Jack Andrews moved out at the beginning of October of 1957. [12]

Jack Andrews relocated his operation to 2029 Portage Avenue in the Deer Lodge area. A later move to 3223 Portage Avenue in the Kirkfield Park/Westwood area negated the long tramp’s claim that it was “54 miles west to the next drug store”; Jack Andrews’ business was a mere 1-1/4 miles (2 km) west, a three-minute drive. A different kind of herbalist business is there now: a Cannabis store.

By February of 1951 Carman Ruttan was advertising his own new location: 1675 Portage Avenue at Madison Street.

|

| In 1951 Carman Ruttan moved his home and business to a more substantial glass and brick building in a busier location. (Trib, Feb. 3, 1951) |

|

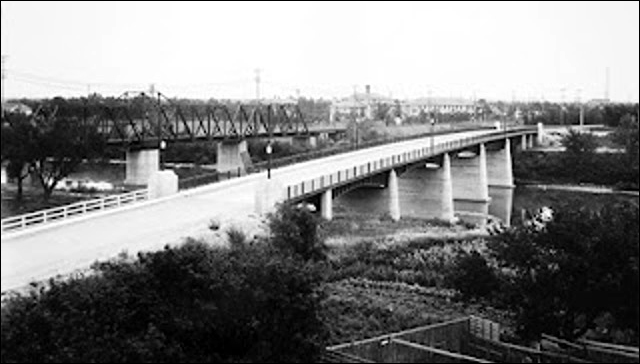

| Looking south across the original St. James Bridge, August, 1937. [15] |

By 1960, the old St. James Bridge was a two-way bottleneck trying to handle over 21,400 vehicles per day. [16] Increasing traffic to Polo Park, the arena, stadium, airport, and points north only added to the congestion. The solution was a new northbound span built next to the old Madison Street bridge, which would then be southbound only. The new bridge opened on December 15, 1962. With approaches and an overpass, it had been a massive construction project.

|

| Ruttan’s property on Madison Street had to go. It was clearly in the way. (Google maps) |

Ruttan’s building was among the more than 20 businesses and 65 homes that were expropriated ahead of the bridge construction. Most were on Madison, and the two streets to the west of it: Kensington and Bradford. Specific addresses were not confirmed well ahead of time. St. James mayor Thomas Findlay told the Free Press, “What we want to do is protect the homeowners from the speculator who comes along and buys the property for a lot less than it is worth, then sells it to metro for more than it is worth.” [17]

Findlay acknowledged that some owners would profit, while others would “lose their shirts.” In the newspaper’s list of several businesses in the cross hairs, Carman Ruttan Drugs was the first mentioned.

Businesses liable to be removed for the bridge and its approaches from Madison west include: Carman Ruttan Drugs, Powers Regulator Co., Winnipeg Piano House Ltd., Mutual Acceptance Corporation Ltd., Allstate Insurance Co., Progress Painting and Decorating Co., Canada Diebold Safe Co., Monarch Factory sales and Service Ltd., Dr. A. Goldstein, Chicken Delight of Canada Ltd., Bells Frozen Foods Ltd.

From Kensington west: St. John Ambulance Council for Manitoba, Snap-on-tools of Canada Ltd., St. James Car Mart, St. James Auto Service.

The same article said, “The businesses along Portage Avenue will have to take care of themselves. The mayor said that St. James wanted to help them but most of them had their own lawyers and would do as they were advised.”

|

| Photo from 1964, two years after the new St. James Bridge was completed. Unlike Ruttan’s building, the Viscount Gort Hotel, built in 1960, was spared, but wound up surrounded by lanes of traffic [18] |

Understandably, Carman Ruttan’s ads strongly suggest he was not at all happy about having to move from Madison Street back to his old address. It was not easy to relocate his home and business, and clearing out the stockroom was a challenge in itself. He had every reason to feel disgruntled.

|

| Free cod liver oil! Anyone? Anyone? (WFP, Aug. 9, 1962) |

|

| It seems no one was lining up for free cod liver oil. (Trib, Aug. 27, 1962) |

|

| This ad gives a glimpse of the many products in the drug store. Cod liver oil remained on the shelves. (Trib, Sept. 18, 1962) |

|

| Ruttan did not rebuild. He took a long tramp back to 2579 Portage Avenue and stayed there. (WFP, Dec. 12, 1962) |

|

| The moving date was only 10 days away. The walls weren’t closing in, they were coming down. (Trib, Dec. 21, 1962) |

|

| Ads didn’t usually include a phone number, but a new one needed mention especially when the business relocated. (Trib, Mar. 7, 1963) |

|

| This small ad ran often in the brutal winter of 1965–66. It was oddly prescient. On March 4, one of the worst blizzards in Manitoba’s history struck. (WFP, Feb. 21, 1966) |

|

| The blizzard’s wind and heavy snow brought down the canopy of this Deer Lodge drug store at 2061 Portage Avenue east of Carman Ruttan’s. [19] |

Carman Ruttan had been working for over 35 years and was 72 years old when he placed a help wanted ad:

|

| Ruttan had employees, but no succession plan. He never retired. (WFP, Sept. 9, 1971) |

Henry Carman Ruttan

Always curious and industrious, H. C. Ruttan showed great promise from the start. The University of Manitoba 1918–1919 yearbook gave this graduate profile of its gold medal winner in Pharmacy:

Carman is a member of an old Canadian family, his great grandfather having sat in the first assembly of the Confederation of Canada. Likewise Carman sat in the U.M.S.A. council as Senior Stick for Pharmacy, but his duties were not limited entirely to this office. During this year he was a member of the Y.M.C.A. Executive for Manitoba University, second vice-president of the Varsity Curling Club, a member of the Scientific Club, and always managed to be present at all social functions.

Although born in Prince Edward County, Ontario, and having spent his first happy years in the East, he received the major part of his education in Winnipeg, graduating from Kelvin in 1915. While attending Kelvin, Carman decided to enroll in Pharmacy, and consequently started working several nights a week, and he is still working. He is just as enthusiastic as ever about his profession as when he started, and let us all hope that much will be heard from him in later years. [20]

Ruttan was born on December 27, 1898 in Sophiasburgh, Prince Edward County, Ontario. He married Alberta Elizabeth Roberts in Winnipeg on November 16, 1922. The couple had two daughters, Lillian and Joanne. On March 18, 1947 he married Anna Dorothy O’Keefe in Montana.

Ruttan died at age 74 on December 1, 1973, five months after his wife’s death on June 28. They are buried in the St. James Cemetery.

|

| Carman Ruttan’s obituary. He and his wife Anna both died in 1973. (WFP, Dec. 3, 1973) |

Ruttan would have been disappointed to learn that China did not take the store’s contents as his will specified. Instead, the University of Manitoba, his second choice, accepted the estate’s herb collection.

|

| It is unfortunate that Ruttan’s formulas were lost when he died. It would be interesting to explore what the University of Manitoba still has. (WFP, July 26, 1975) |

Following Ruttan’s death, the drug store was purchased from his estate by Donald Jacks, and used as the national headquarters for his chain of tax preparation offices (U & R Taxes). Mr. Jacks had lived in Brandon as a boy, and always watched for the Long Tramp when the family drove home from Winnipeg. Don’s son Al recalled the building and its mural, telling Buchanan:

When we first bought the building we were approached by the media and asked if we were going to paint over it. No way! It’s a historic landmark!

I was given the task of cleaning out the building. I found all kinds of old recipes, and racks and racks of bottles with stuff in them that didn’t have names on them, only numbers—he must have used some kind of code system to keep his works a secret.

We had Harry Schimke, my wife Evelyn’s father, repaint the Tramp. He was a masonry serviceman that did bricklaying, but was also an artist and was willing to try his hand at repainting the tramp. We repainted it right away soon after taking possession of the building in about 1977. [21]

The result is essentially the mural we see today. No longer a drug store, and with others nearby, the sign reads “54 miles to Portage” instead.

The building changed hands in 1992, when Brian Webb bought it from U & R Taxes. In 1994 he had the Long Tramp registered as a trademark. That same year, the mural was restored. When stucco was applied to the building, the mural was carefully masked off and saved. [22]

|

| The mural being restored in 1994. (L-R): Mike LaBelle, Alfred Widmer, Stef Johnson. Photo by Joe Bryska, Winnipeg Free Press (posted on the Murals of Winnipeg website). [23] |

Sources

- Bob Buchanan (1953–2023), “2579 Portage Avenue,” The Murals of Winnipeg. http://www.themuralsofwinnipeg.com/Mpages/SingleMuralPage.php?action=gotomural&muralid=1

- Manfred Jager, “Famous Portage Avenue landmark to continue his 75-year-old tramp,” Winnipeg Free Press Community Review, October 5, 1994.

- D. McDougall, ed., The History of Pharmacy in Manitoba, 1878-1953, The Manitoba Pharmaceutical Association, 1954, p. 66.

- Fred Morris, “Aldine Street best-known for famous mural,” Winnipeg Free Press Community Review, October 5, 2022. https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/our-communities/correspondents/2022/10/05/aldine-street-best-known-for-famous-mural

- Bob Buchanan

- Bob Buchanan

- Lorraine Arnott, “Herbalist’s mural is a city landmark,” The Senior Paper, April 2012. https://theseniorpaper.com/online/2023/02/herbalists-mural-is-a-city-landmark/

- Bob Buchanan

- Lorraine Arnott

- Jimmy King, “Night Beat,” Winnipeg Free Press, August 17, 1974, p. 13

- Bob Buchanan

- Bob Buchanan

- H.M. Gousha Company. “Street Map of The City of Winnipeg Manitoba, 1961” in Manitoba Historical Maps, Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/manitobamaps/3922733505

- John Dobbin, “Viscount Gort, Polo Park and St. James Bridge History,” Observations, Reservations, Conversations blog. https://johndobbin.blogspot.com/2019/08/viscount-gort-polo-park-and-st-james.html

- “Historic Sites of Manitoba: St. James Bridges (Century Street, Winnipeg),” Manitoba Historical Society. https://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/sites/stjamesbridge.shtml

- “Historic Sites of Manitoba”

- “Evict 65 For Bridge,” Winnipeg Free Press, October 9, 1961, p. 3

- John Dobbin

- Ken Kristjanson, “March 4th 1966 Blizzard,” Memories from the Lake, March 4, 2022. https://www.memoriesfromthelake.net/blizzard?lightbox=dataItem-l0pjcx3r1

- University of Manitoba, Ontario History, https://www.ontariohistory.org/university-manitoba-1919.htm

- Al Jacks, quoted by Bob Buchanan

- Bob Buchanan

- Manfred Jager