Naturally, settlers needing to build houses looked to their homelands for inspiration, as author Shannon Kyle, an instructor at Mohawk College, explains:

Since a great many of the early settlers in Ontario were from the United Kingdom, it is not surprising that their buildings often contain details found in English Gothic and medieval architecture. Many elements of stone buildings in England are translated into wood on cottages and smaller residences in Ontario Gothic Revival buildings. The overall effect is eclectic and usually ornate. The Gothic Cottage is probably the most pervasive Ontario residential style prior to 1950. [1]

Kyle has noted that, “The materials used to finish these cottages are always local. The central doorway, central gable and decorative vergeboarding are found on all such cottages, but reflect the local craftsmen.” She explains how this provides an “easy dating tip” for brick homes:

Brick was made on the property with local clay. Clay west of Woodstock in London, Harrisburg, Ayre, etc. is yellow because of the amount of lime in the soil. In Caledon it is red because of the iron. In Hamilton it is orange. East of Toronto it is mostly darker orange but not as dark as in Caledon. Brick is very heavy. No one would be likely to sacrifice the health of their horses or oxen to travel five or six days to another country where the brick is of a different colour. If there are two different colors of brick, the house was constructed after trains could carry the brick from one town to another—from 1853 on, depending on location.

The Reid home is one such gem that exemplifies the distinct “Ontario cottage” (aka “Ontario house”) architectural style:

The Ontario cottage is a style of house that was commonly built in 19th century Ontario, Canada. The Ontario cottage became popular in the 1820s and remained a common style until the end of that century. They were mainly built in rural and small town areas, less so in larger cities. This was the period in which European settlers first populated the interior of the province, and throughout it Ontario cottages are some of the oldest houses.

An Ontario cottage is essentially a regency-style structure, with symmetrical, rectangular plans. The style was efficient and easy to build for settlers with limited resources. The typical cottage had one-and-a-half storeys and large windows, made possible by relatively cheap mass-produced glass. The most distinctive feature of the Ontario cottage was the single gable above the door in the centre of the building. By the second half of the 19th century Gothic had become the most popular architectural style in Canada. Many Ontario cottages built during this era incorporate Gothic ornamentation, most often added to the gable. [2]

|

| The Clendenning Bayview Farm home in Blenheim, Ontario. Built in 1877, it features a fine example of a Gothic bargeboard. These decorative elements added character and helped strengthen the gable. |

The Donald Reid House c. 1875

Elderslie Township Concession 5 Lots 12 & 13

Here is the quintessential Ontario Gothic farmhouse, standing in an open field and framed by huge old poplar trees twice its size. The total effect of the house in its site is one of severe restraint. However, white-painted brickwork around the openings, the corners and the beltcourse adds a note of cheerfulness to the utterly simple design of the structure.

Peter Reid (1829–1896), a pioneer blacksmith, married Christena Taylor (1839–1925) in Paisley in 1860. The original blacksmith shop on the property is still intact and in use. This farm has been in the Reid family through the generations represented by Donald Reid, Wilfred Reid, and now Scot Reid.

This enduring family history and the vernacular architectural design of the house combine to tell a story of the character of rural Ontario. It is a story of the steadiness, resolve and optimism of the first settlers, and their descendants’ respect for tradition and family. [3]

|

| The Donald Reid House today [3] |

As Cathcart notes, the house is a quintessential Ontario Gothic farmhouse. Its style harkens back to designs featured in The Canada Farmer.

|

The aim of The Canada Farmer’s editors and authors was to spread what they perceived as good taste and architectural ideas to those in rural areas beyond the reach of architects. [6]

|

| James Avon Smith, Jr. (1832–1918), ca. 1890 [7] |

Gothic architecture’s popularity would inevitably impact Canadian popular taste, but also because most of the colony’s earliest architects were trained in England. Like in England, Gothic was used most notably in church architecture and in prominent secular buildings like the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa. […] Gothic was believed in the nineteenth century to be the most adaptable of architectural styles. Understood then as a counterpoint to classical architecture, Gothic was seen to have fewer precise rules. [9]

|

| One of Smith & Gemmell’s best known designs, the elaborate (and very Gothic) Knox College, Toronto, 1873–75. [10] |

While his city commissions were substantial and elaborate, Smith was equally at ease promoting simpler designs for The Canada Farmer readers. He was not trying to drum up business (his name is rarely mentioned); rather, he wished to promote attractive, efficient, and neat design. He considered the needs of rural folks to be unique and deserving of attention.

Smith’s modest farmhouse designs were neither new, nor revolutionary (and he did tend to borrow ideas from existing pattern books). Nevertheless, the Ontario cottage style became very popular, largely due to his “Rural Architecture” column in The Canada Farmer journal. Smith’s building designs, complete with illustrations and floor plans, were accessible to a receptive rural audience. That was new.

In an early column in 1864, Smith profiled “a small gothic cottage” concept:

|

| The architect specified red brick with white quoin corners, built on a raised terrace. |

|

| Outdoor plumbing, of course, was the norm when this plan was published on February 1, 1864. |

This building can be constructed with stone, brick, or timber. It is a dwelling suitable for a small family, the main building having a hall six feet wide running through the centre and entering the kitchen; on the left side of this hall is a large living room or parlour, 11 x 19, and store room, 14 x 7; on the right are two bedrooms, one 13 x 14 and the other 11 x 14; in the rear addition is a large kitchen, a pantry and bed-room. […] The window-sills and the drips over the front door and windows, could be of dry pine, painted and sanded, but stone would be better. A small gable is raised over the front door, surmounted with a turned pinnacle, and having a simple piece of tracery fastened to the under side of the cornice, and in the centre of this gable is a small trefoil window to give light and ventilation to the garret. […] The cost of a cottage of the above description would not exceed $1,000. […] Size of main building, 36 x 28. Kitchen extension, 21 x 22. [11]

In other issues of The Canada Farmer, Smith presented additional rural designs, including a “Suburban Villa or Farm House,” (May 16, 1864), “A Two-Story Farm-House,” (April 15, 1865), and “A Neat Country Church” (January 15, 1866) that was as basic as could be.

Smith’s November 15, 1864 column presented a 1-1/2 storey design he called “A Cheap Farm House.” Intended for a large family, it included a cellar for food storage. The article gave dimensions, material and construction details, but said they were “general specifications.” A timber version would cost between $600 and $800 (less than $15,000 in 2002). Tips for reducing costs included postponing the kitchen construction, and substituting materials for cheaper ones. The extra cost for adding shutters, a verandah, fencing, and landscaping was encouraged. Kitchens were sometimes built away from the main structure to reduce fire risk, and to isolate cooking smells and summer heat.

|

| Five bedrooms and a parlour for $800 if built of timber—a good deal. |

As Smith concluded:

It is rather by attention to the aggregate of inexpensive details, than by large outlay on one particular object, that the comfort and attractiveness of a country house are secured. We are persuaded that a little more regard for what many consider trifles unworthy of notice, would yield a large return of real enjoyment and satisfaction. [12]

In his August 15, 1865 column Smith returned to the cottage, presenting “A Cheap Country Dwelling House”—a 1-1/2 storey version that resembled his earlier design from November 1864. This one featured four bedrooms.

It is designed so as to be built with either brick, stone. or wood. The exterior, as will be seen, presents a neat and graceful appearance. The front is broken by raising a small gable over the front door, and is ornamented with a pinnacle, and arched barge board. The front door entrance is protected from the weather by a projecting hood board supported on ornamental cut brackets, and covered with shingles cut in patterns. The front and end windows are furnished with moulded drips, with return ends.

The plan is in the form of an inverted T. The main building is 31 feet long by 21 feet wide, with a rear addition for the kitchen, 15 feet by 16 feet. The main building is divided as follows. At the entrance, a small vestibule adds to the comfort of the rooms, by keeping out the cold, when the front door is opened. To the right of the entrance is the sitting or dining room, 14 by 20 feet, with a pantry in connection, under the stairs, and to the left of the entrance a large airy bedroom, 20 by 12 feet. There will be a cellar under the dining-room, with an entrance to it under the stairs. […] The kitchen is entered from the dining room, and has an outside entrance in the side, as shown in the side elevation. Upstairs there are three bed-rooms, a lumber-room, and wardrobe. The lowest part of the bed-room ceiling is five feet, and the highest 8 feet, but any height can be got by increasing the dimensions. The bed-rooms can be heated by passing the stove pipes up through the floor and into a flue coming two feet under the attic ceiling. This arrangement saves the expense of carrying the flues up from the foundations. A house of this sort, if built where the materials can be obtained at reasonable prices, could be finished for about four hundred dollars.

Smith knew his audience; he was Scottish himself.

Four hundred dollars was a good price for a smart and attractive design. Not mentioned in the text was another reason his design was so popular. It was cheap because “property tax laws in Upper Canada were based on the number of stories in a house. The gothic 1-1/2 storey cottage allowed for two levels at a cheaper tax rate, with a window in the gothic gable above the entrance door. As the century advanced the pitch of the roofs increased to allow for more living space and stay within the tax limits.” [13]

The basic design was not unfamiliar, and was simple enough for local contractors and masons to recreate and modify. The plans could be readily personalized without needing an architect. Creative variations abound, but the identifying features of a Gothic revival cottage always harken back to James Avon Smith’s 1865 concept.

Features of the style: [14]

- A steeply pitched roof and gables with decorative bargeboard (gingerbread trim under the eaves). The steep pitched roof helped shed snow, too.

- Gable at the centre of the symmetrical front façade and/or over arched windows

- A window over the front entrance

- Transoms aside or above the front door

- Porches (if any) with elaborate Victorian details (turned posts, arches, brackets)

|

| Variations on a theme in Ontario. [15] |

|

| A fine and familiar-looking example that would make James Avon Smith smile. [16] |

But, of course, we have a favourite:

|

| An early photo of the Reid homestead. L-R: Donald, Neil, Annie and mother Christena. [17] |

|

| An early but undated photo from Annie Reid’s own album. L-R: Donald, mother Christena, and Kate. A guess is that the baby is Kate’s daughter Christena (b. 1908). |

|

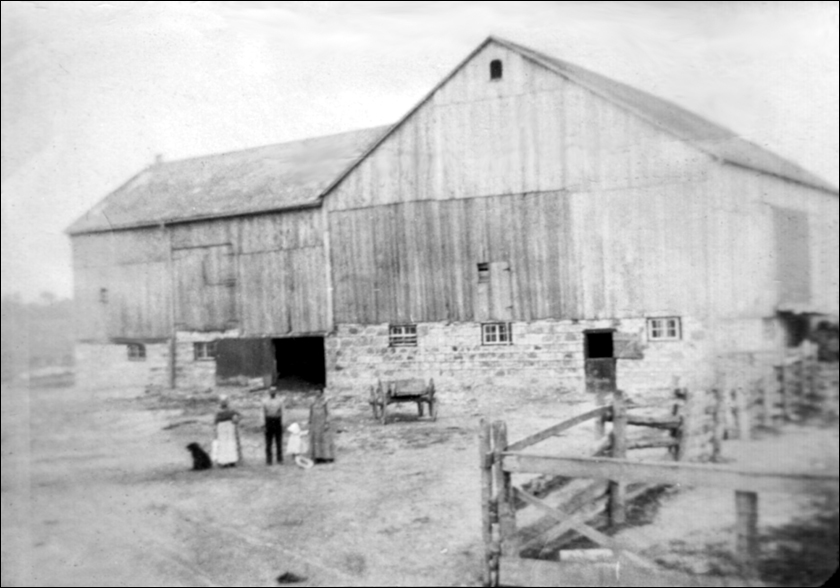

| The Reid barn/blacksmith shop was enormous. Also from Annie’s album, this photo suggests the toddler is Kate’s daughter. |

|

| The Reid farm in 1942 |

Sources (retrieved Dec. 3, 2024)

- Shannon Kyles, “Gothic Revival Cottage,” Ontario Architecture. http://www.ontarioarchitecture.com/gothicrevival.html

- “Ontario cottage,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ontario_cottage

- Ruth Cathcart, The Architecture of a Provincial Society: Houses of Bruce County, Ontario 1850–1900. Wiarton: The Red House Press, 1999, p. 61

- For an example of the April 15, 1869 issue, see: “Record of the Week: The Canada Farmer,” blog post in The Archivist’s Pencil, Sept. 28, 2018, http://archives-archtoronto.blogspot.com/2018/09/record-of-week-canada-farmer.html. Full digital issues are online at Canadiana by CRKN, https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_04206

- Dr. Jessica Mace, “Beautifying the Countryside: Rural and Vernacular Gothic in Late Nineteenth-Century Ontario,” Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada, Dalhousie University, Vol. 38, Issue 1, 2013, pp. 29-36, https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/items/ed7169de-a9f0-48dd-8408-55886a1e9cfd

- Dr. Jessica Mace, “ ‘A Cheap Farm House,’ c. 1864–onward,” in Smarthistory, September 2, 2002, https://smarthistory.org/a-cheap-farm-house-1864-onward/

- James Smith, digital image #10010417 ca 1890, Ontario Ministry of Government and Consumer Services, Archives of Ontario Visual Database, copyright Queen’s Printer for Ontario, in Janice Hamilton, “James Avon Smith, Toronto Architect,” Writing Up the Ancestors, June 21 2017, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2017/06/james-avon-smith-toronto-architect_21.html

- “James Avon Smith,” Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada, 1800–1950, http://www.dictionaryofarchitectsincanada.org/node/1313

- Dr. Jessica Mace, “ ‘A Cheap Farm House,’ c. 1864–onward,” in Smarthistory, September 2, 2002, https://smarthistory.org/a-cheap-farm-house-1864-onward/

- “Knox College, Toronto, Can.” Postcard, Toronto Public Library, Digital Archive, https://digitalarchive.tpl.ca/objects/380978/knox-college-toronto-can?ctx=06f708dc165402409ee3b0d034e1f6d7859dae27&idxKnox Co=11

- “Farm Architecture,” The Canada Farmer, Vol. 1, No. 2, February 1, 1864, pp. 20–21, https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_04206_2/2

- “A Cheap Farmhouse,” The Canada Farmer, Vol. 1, No. 22, November 15, 1864, pp. 340–341, https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_04206_21/5

- “The Gothic Revival and the ‘Ontario House’,” Ontario Architectural Style Guide, University of Waterloo, January 2009, p. 9, https://www.therealtydeal.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Heritage-Resource-Centre-Achitectural-Styles-Guide.pdf

- Steven Fudge, “The History Of The Ontario Gothic Revival Cottage,” April 21, 2017, https://urbaneer.com/blog/ontario_gothic_revival_cottage.

- “Gothic Cottage,” album, Ontario Architecture, http://www.ontarioarchitecture.com/gothicottage.htm

- Barbara Raue, Chatsworth and Grey Bruce Ontario in Colour Photos, 2018, http://barbararaue.ca

- Mary McKay, Far Spread the Sparks from Cantire, c1993, p. 208